Columbia University recently announced the 2020 winners of the Pulitzer Prize. The awardee in the field of history is Sweet Taste of Liberty by W. Caleb McDaniel. It is, in the words of the Pulitzer Prize description, “a masterfully researched meditation on reparations based on the remarkable story of a 19th century woman who survived kidnapping and re-enslavement to sue her captor.” The title of a 2019 New Republic review of the book styles it “an early case for reparations.”

This commentary is not meant to be a review of the book itself, which I haven’t yet read. It is by all accounts an impressive achievement—a well-crafted narrative built upon original research into what had been a little-known episode in the post-Civil War period. It tells the remarkable story of Henrietta Wood, a freed slave who was kidnapped back into slavery in 1853 and later successfully sued her captor for damages and lost wages.

The problem is not the historical accuracy of the account but the uses to which it has been put. The author has encouraged the application of his work to the contemporary debate over reparations—the financial payment to African-Americans to atone for the slavery, racism, and discrimination that have suppressed black economic progress throughout American history. In a New York Times editorial, McDaniel suggested that Henrietta Wood’s story “challenges the primary way that Americans have tried to repair slavery and segregation since: apologies without checks.”

For those who advocate “checks” (reparations) along with apologies, the Emancipation Proclamation, Reconstruction and its constitutional amendments (13th, 14th, and 15th), and the victories of the Civil Rights Movements are not enough. Outlawing discrimination based on race is not enough. Even demonstrably altered attitudes—polling since the 1950s shows that racism has declined dramatically in the United States—are not enough. Slavery and racism, in their view, have had a substantial and lasting negative effect on the ability of black Americans to accumulate wealth and achieve economic progress. Thus payment of damages from that part of American society (white) that has benefited to that part of American society (black) that has suffered is one necessary ingredient of any recipe for reaching justice and resolution to the country’s persistent racial tension.

The case for reparations is not without foundation. Slavery and racism did damage black economic prospects is grave and lasting ways. Many conservatives rightly point to the prevalence of family dysfunction among African-Americans as the primary cause of racial disparities in economic wellbeing but fail to acknowledge that the institution of slavery, in which fathers and mothers and children could be torn from each other at will, did catastrophic damage to the integrity of black families. Similarly, those who are skeptical about the idea of “systematic racism” would do well to explore the history of the interplay of financial institutions and government in mortgage and insurance practices in American cities in the post-World War II era. White home buyers and business owners did enjoy systematic advantages in their quest to build wealth in the prosperous postwar period. There are lessons to be learned from this history.

But it doesn’t necessarily follow that it would be just, prudent, or even feasible for “white America” to pay “black America” in restitution for slavery and its legacy. In the Henrietta Wood case, a specific person suffered specific damages and the person who inflicted those damages paid compensation. The contemporary case is much different. To begin, there are—as some reparations advocates concede—enormous challenges of definition and delineation. Who pays whom? Are all Americans of non-African descent “white”? Are all Americans of African descent entitled to reparations? There may be a (weak) argument that a recent immigrant from Nigeria suffers in a vague, indirect way from the racism that is endemic in American culture, but surely that case is far different from that of a direct descendant of slaves. What if that Nigerian is the descendant of a tribal chief who raided competing West African tribes and sold his captives to British slave traders doing business in the New World? It gets complicated.

Looking at the other side of the ledger, how do we justify payment from “white” Americans whose ancestors were not slaveholders but serfs in Russia, farmers in Ireland, or shopkeepers in England? Reparations argue that racist structures have nonetheless benefited these whites, but again, it’s hard to justify lumping these groups together with white families whose wealth is inherited from slave plantations.

These complications point to the problematic nature of the whole project of reparations for distant and general wrongs. Justice is difficult enough to achieve when the parties to conflict are still alive, the harm is fresh, and evidence and witnesses abound. This is one of the reasons for statutes of limitation: As time passes, it is increasingly difficult to perform an accurate assessment of wrongdoing, its effects, and appropriate restitution.

The current push for reparations is an example of what Thomas Sowell called “the quest for cosmic justice”—an attempt to right the wrongs of centuries of history and redress the evils of human nature. If we’re out for justice, why stop at antebellum slavery? There have been a lot of other injustices in American history. Those suffering economic damage at the hands of other Americans would include (among many other options) Native Americans, Chinese-Americans, Japanese-Americans, Irish-Americans, and Hispanic-Americans. Moving from ethnic to religious identification, it would include Roman Catholics, Jews, and Muslims.

The list is endless, and so the quest never ends. Cosmic justice can’t be achieved and the attempt to do so will simply generate more conflict. Black Americans, like all people, deserve the “sweet taste of liberty,” but reparations are a bitter fruit.

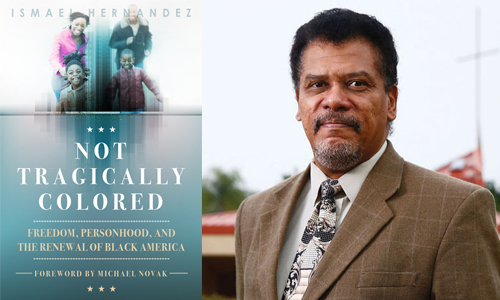

There is a better way forward. Freedom and Virtue Institute president Ismael Hernandez describes it in his book, Not Tragically Colored. When he first arrived in the United States from Puerto Rico as a college student, he carried along the baggage of victimhood: “American whites had not yet had the opportunity to oppress me, and I was already considered a victim, a wounded casualty of a race war that tied my future to an identity as victim.” Through reading (Thomas Sowell among others) and experiencing the generosity and freedom of American culture, Ismael came to see his new home as a land of opportunity. America didn’t change but Ismael’s attitude toward it did.

He understood well the ugly underbelly of American history and the harsh, enduring evil of racism, but he chose not to be defined by his racial status. “Race consciousness is offered as an infallible sign of authenticity, luring us to abdicate responsibility and liberty.” Rejecting group identity, he embraced a Christian anthropology that upheld individual dignity and the power of human choice. “No matter how many times we are shamed by those telling us that the boundary of race must not be crossed, we must press forward. The call is to affirm our individuality and our capacity to choose our path in life in spite of social pressures. The task is to be free.”