As is well known, for Karl Marx work was a source of alienation. In the Christian tradition, too, the Genesis account teaches that the hardship of toil is a result of sin. Everyone has some experience with work as drudgery, indignity, or burden.

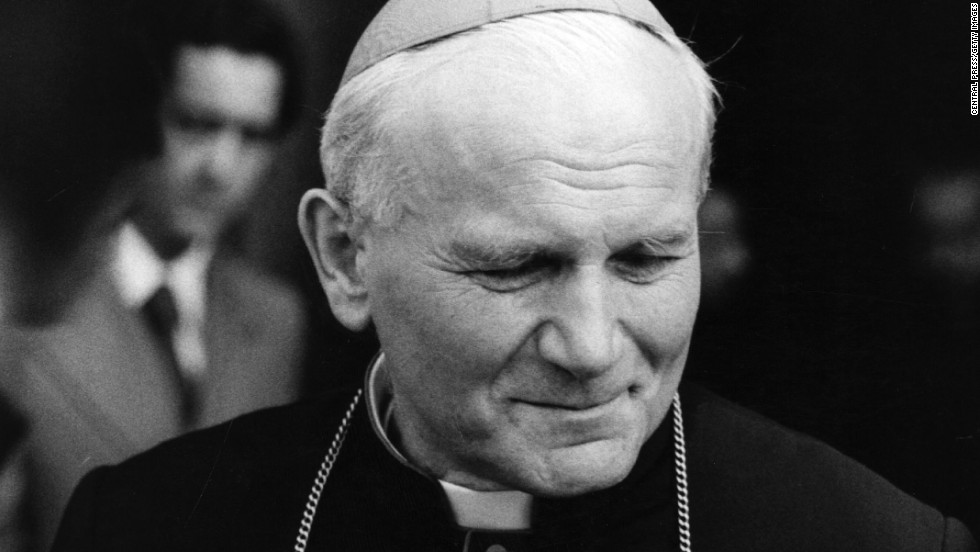

But there is another side of labor. It can also be fruitful, rewarding—even healing. As Pope John Paul II explained in his 1981 letter on human labor, “Work is a good thing for man—a good thing for his humanity—because through work man not only transforms nature, adapting it to his own needs, but he also achieves fulfillment as a human being and indeed, in a sense, becomes ‘more a human being.’” We can see this dimension of work—its dignity and benefit—in the story of Constance from South Sudan.

A middle-aged, married woman with four children, Constance is no stranger to hard work. Besides managing her own household, she has provided care for more than twenty orphans in her extended family. Outside the home, she oversees a trauma healing organization that assists women in Protection of Civilian (POC) camps, refuges for those suffering from the country’s civil conflict. It is thought that almost all women in these camps have been victims of sexual abuse of some kind.

“increase the common good developed together with his compatriots, thus realizing that in this way work serves to add to the heritage of the whole human family, of all the people living in the world.”

The healing groups meet regularly and provide a time for sharing and prayer. They also provide an opportunity for remunerative work. The organization runs a micro-loan program, whereby women can obtain small loans to start businesses such as bakeries or clothing shops. Like many such programs, the micro-loan operation is highly personal—and highly effective. Everyone knows who is getting what, and everyone cares about keeping the fund solvent. In the several years that Constance has managed it, there has been only one default.

Constance previously worked for a government agency and criticizes the dominant mentality there: “a myth that women couldn’t do anything for themselves.” Instead, she found that “they had a deep strength. They brought order out of disorder.”

This experience spurred Constance to empower the downtrodden women of South Sudan to better themselves. As women begin providing for themselves and succeeding in the marketplace, their confidence in themselves and their abilities grows. They contribute not only to their own wellbeing but also to that of their community, highlighting yet another important dimension of work: its social impact. Through work, John Paul wrote, the person seeks to “increase the common good developed together with his compatriots, thus realizing that in this way work serves to add to the heritage of the whole human family, of all the people living in the world.”

In South Sudan, all of this is accomplished in the face of manifold challenges, but such obstacles are not insurmountable when confronted with determination. “We can make a difference,” Constance says. “We can learn to work.”

For Constance and the women in her ministry, labor is not cursed or alienating but healing. It does not rob dignity but restores it. It is something to celebrate.

The author acknowledges and thanks to Gabe Hurrish of Maryknoll Lay Missioners for sharing Constance’s story.