Recently, a politician’s words gave occasion to pondering on the meaning of identity using the now infamous phrase “you ain’t black.” His words are not unique to him but a reflection of a double standard where ethnic identity is tied to political affiliation or ideology. This connection affects also questions of poverty, where the poor and those who want to help also are expected to toe a certain line. It appears that what is primary is an ideological goal and various causes are merely instrumental toward the said ideological end.

There is a history of ideologues, mostly but not exclusively of the left, immersing themselves into causes. Since the late 1800s, for example, Progressives were at the forefront of otherwise commendable causes but not intent on amending or reforming the system. Instead, they saw the cause as useful toward the end of destroying capitalism—the only true goal for ideologues using Marxist readings of history. Causes are mere emblems showcasing the inherent alienations in the capitalist system. The causes are the proximate instrumental end, but the total transformation of the system is the ultimate end.

Progressives were involved in the abolitionist, women’s rights, universal suffrage, unionization, civil rights, social work, workers’ rights, gay rights, the sexual liberation, and now in the gender ideology. These involvements were not attempting at making the present order better, although in their conception each was a positive step toward the all-encompassing end but attempts at destroying it and bring about a new one. Their aim was to create liberation fronts that would increase the consciousness of those seen as “oppressed” by forces inherent in the class structure of the social order.

Having placed this framework, let us discuss the politician’s words and the larger ideological understanding that informs the words and ties blackness to the support of a given political party or ideology. To insult a black person whose political allegiances are on the Progressive sphere would be racist and abhorrent because that stance advances their ideology. However, when the insult is proffered against a black conservative or black libertarian or even one who wants to debate whether or not he is to align with Progressivism, is not seen as offensive, as supporting that individual does not advance the Progressive ideological goal. After all, in the Progressive understanding of what is a priority, individual affronts or needs are not at the center—as classes move history. Each person is but a drop within the great wave of revolution. In fact, it might be advisable to attack a drop who seen as nonconforming.

A similar situation occurs when a black person does not place ethnic identity as primary, at the core of his individual identity. To deny centrality to the core collectivist understanding of identity for a person of an “oppressed” group is to deny the importance of his ethnic identity—thus worthy of excoriation and isolation. Class consciousness takes precedence over individual consciousness.

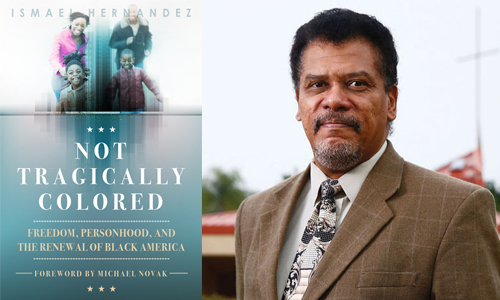

That is a clever use of the straw man fallacy but perfectly consistent with the Progressive view of society, parasitic as it is of the Marxist understanding of history. What blacks whose ideology is not of the left say, especially those akin to the natural law tradition, is that race or ethnicity are not at the heart of identity. The individuality of every human being comes first and the elements of identity intrinsic to their humanity take precedence over social constructs. We are human beings—male or female—and that sexual identity is primary and intrinsic. Further, before sin enters the scenario, we are given each other in the biblical narrative—taken as a pre-historical anthropology, not as a religious account. Marriage and the family are the most basic and important communities, communities of love and life which are natural spontaneous orders, not mere social constructs.

One thing is to discuss the relative place of ethnic identity as a social construct within the constellation of “identities,” or better, “identifiers” that make up our social being and another thing is to deny that one is black. Often, people who deny ethnic identity as the primary identifier say that they are Americans, instead of African Americans. That also is a discussion of the relative place of ethnic ancestry vis a vis other identifier, such as national identity. It is not a negation of the anyone’s ethnic (say cultural) heritage. The idea that one’s blackness or African ancestry must be affirmed at every turn is a linguistic subset of the false narrative of Afrocentrism placing blacks as in eternal Diaspora, foreigners in the American exile, and not rightful members of the only society they have ever known, America. If one perceives the collective identity and destiny of blacks through that prism, insulting some nonconforming members is a duty.

One thing is to discuss the relative place of ethnic identity as a social construct within the constellation of “identities,” or better, “identifiers” that make up our social being and another thing is to deny that one is black. Often, people who deny ethnic identity as the primary identifier say that they are Americans, instead of African Americans. That also is a discussion of the relative place of ethnic ancestry vis a vis other identifier, such as national identity. It is not a negation of the anyone’s ethnic (say cultural) heritage. The idea that one’s blackness or African ancestry must be affirmed at every turn is a linguistic subset of the false narrative of Afrocentrism placing blacks as in eternal Diaspora, foreigners in the American exile, and not rightful members of the only society they have ever known, America. If one perceives the collective identity and destiny of blacks through that prism, insulting some nonconforming members is a duty.

However, what black conservatives and other non-Progressives affirm is that their identity is not determined by ethnic self-appointed gatekeepers of blackness. Each person stands sui generis as an individual in the midst—not apart from—any group. His individuality is injected with a history and a culture, but such is thus not exhaustively. As our individuality as persons does not disappear, there flows from such magnificent personalist anthropology an intellectual diversity that enriches the group. Such anthropology, however, is anathema for the Progressive. That we have a right to affirm who we are as Americans and as black people and we have a right to dissent from the political majority within the community and from the theories of race advocated by others remains a truth that we shall not surrender. We concede to no one the right to determine who we are as individuals or to shape for us what it means to belong.