Admonitions on how to bring about peace in the world are not new. As early as 385AD, the Roman military expert Vegetius in his influential military treatise wrote, “Igitur qui desiderat pacem, praeparet bellum” (“Therefore let him who desires peace prepare for war”).[1] To this day we are preoccupied with justice and peace and how they interrelate. This is why we must ask if the slogan “No Justice, No Peace” is reasonable. The origin of the slogan is unclear, but various versions place it in the context of racial antagonism and protests in the mid-1980s.

The slogan can be understood either as a conditional or a conjunctive statement. The conditional renders the proposition as an “if-then” statement, meaning that in the absence of justice peace is not possible. Essentially, a condition of injustice leads to a condition of absence of peace even if war is not present. Injustice triggers alienation, and alienation can lead to disintegration because the right relations between men are disturbed. One can ascertain that it is reasonable to believe that if injustice exists, there is no real peace, and the conditions exist to bring about violence.

In the context of racial politics, however, it becomes more than a statement of fact and reasonable expectation, meaning that if there is no justice, we might not get peace. Instead, it is an invitation to the use of force, as peaceful protest is useless in acquiring justice. As a proposition, it invites people to see a problem within the dialectical understanding that only the use of force will move the “oppressor” to rescind his privileges. It tells people that the existing structures of society cannot possibly attend their quest, as the structures are inherently racist and thus unjust—so the theory of systemic racism explains. It is difficult to see how the conclusion that the social system of America is ultimately and inexorably destined for dissolution can fail to lead us to despair. The conditional renders the use of peaceful protest illusory and ineffective and calls for the framing of the struggle for justice in the right instrumental fashion. It is a call to arms, or better, a call to accept a very specific ideological system as a prerequisite to eventuate justice and peace.

By contrast, the slogan understood in the conjunctive form, states that neither peace nor justice can exist without the other. The conjunctive provides a conclusion: the absence of justice has resulted in a lack of peace. Al Sharpton, for example, has written as much, “‘No justice, no peace’ […] is a way to expose inequality that would otherwise be ignored.”[2]

In other words, the phrase asserts a very specific understanding of an existing structural condition. One must understand that society is unjust and that the violence we see is the necessary result of injustice. As such, one may or may not agree with the assertion that the violence we see is the result of injustice. After all, violence can serve other purposes. Ideologies use violence, and people with personal or group gain in mind use violence.

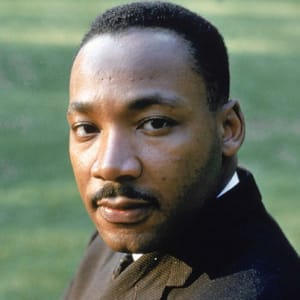

For example, Dr. Martin Luther King understood the substance of the slogan in the conjunctive. The reality of structural racism, still alive and well during his time, motivated him and others to protest peacefully. However, they were met with violence; there was no peace. Notice that he did not accept the slogan in the conditional, at least not in the conditional as presented within a dialectical framework. He believed that peaceful protest had both instrumental and moral value, and violence, even in the presence of actual injustice, was not necessary. Powerfully, Dr. King connected justice to love. He had an optimism about America despite the obvious struggles and difficulties that could easily lead him to pessimism—a pessimism that at times we find in him later on during the movement. Dr. King was also a realist: Racism was real, oppression was real, and it demanded a response. Love was not enough without justice and its pursuits demanded that blacks have the courage to stand for their rights. He saw the plight for justice as righteous and based both in his theology and in his adherence to the principles of justice in the constitution:

“We are not wrong in what we are doing. If we are wrong, then the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God almighty is wrong. If we are wrong, Jesus of Nazareth was merely a utopian dreamer and never came down to earth. If we are wrong, justice is a lie.”[3]

Photo Credit: Howard Sochurek/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Dr. King saw the need to make a case for the reality of structural injustice that necessitated a response that need not be violent but could be violent. In effect, the Black Power movement responded to the same structural reality with a conditional response that saw in the use of force the only effective response to injustice.

In the conjunctive, there is an assertion about a situation that demands a justification. It is reasonable that a state of pervasive injustice will trigger a violent response if those suffering injustices cannot find a remedy—as we asserted to be the case concerning the conditional. The conjunctive is not proposing violence as the solution nor establishing that peaceful protest cannot be an instrumental cause for justice and in turn peace. It, however, warns about that possibility because one cannot exist without the other. Moreover, justice is not the only social good that brings about peace. As Pope John Paul II reminded us, “No one should be deceived into thinking that the simple absence of war, as desirable as it is, is equivalent to lasting peace. There is no true peace without fairness, truth, justice and solidarity.”[4] Special attention ought to be granted to truth. In effect, there can be a claim to justify force built on a false assertion about the presence of injustice.

The determinant question ought to be clear by now: Do the present circumstances merit the conclusion that we live in a systemically racist society that triggers the violence we are now observing? Again, injustice merits a response that needs not be violent and the life and efforts of Dr. King and his movement show it. Dr. King made a case for the presence of injustice and made a case for a courageous but nonviolent response. Are the present cadre of activists led by groups such as Black Lives Matter and Antifa making a case for the present violent response?

We can ascertain, in conclusion, that the slogan “No Justice, No Peace” is not useful without a context and without a justification for the use of violence. Those who use the slogan are at times part of the universe at hand and incapable of seeing that it is possible that their violent response might not be justified. They are involved in a Game Without End where they can run through all possible internal examinations without effecting real change in their consciousness. Only with a radical leap from the paradigm that justifies violence can one see that their response is unnecessary and that the system they deem irreformable can generate from within itself the conditions for its own second-order change.[5]As slogans are synecdoche, they are created for action, not for reflection. They are shouted, not proposed. They are there to mobilize or delude, separating believers from the hoi polloi. Beware of all slogans.

[1] Vegetius Renatus, Flavius. “Epitoma Rei Militaris [Book 3]” (in Latin). The Latin Library.

[2] Sharpton, Al (10 January 2014). “No justice, no peace: why Mark Duggan’s family echoed my rallying cry”. The Guardian.

[3] Cited in Cone, James H., Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare (New York: Orbis Books, 1991) p. 62.

[4] Pope John Paul II, Message for World Day of Peace, issued December 8, 1999.

[5] See Watzlawick, Weakland, Fisch, Change: Principles of Problem Formulation and Problem Resolution (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1974) pp. 21-25.