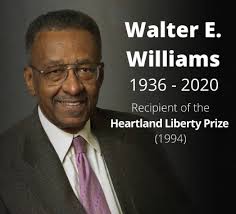

The passing of the great Walter E. Williams is a sad moment for the intellectual life of the nation. He was a towering voice of sanity and courage in a sea of conformity. His voice joined with Thomas Sowell, challenged the shibboleths that pass as tokens of authenticity but are mere instruments of control. They pointed toward a different understanding of race in America and proposed a different vision of what it means to be black in America. Today’s realities of race in America impose on us a new set of commitments. Such commitments represent a departure from the one-dimensional explanations of the liberal/radical racial narrative. The departure is not simply methodological but foundational, not incremental but reconstructive. The thought of Thomas S. Kuhn on the appearance of scientific revolutions can enlighten our discussion here.

In his Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn tells us that scientists routinely operate within paradigms providing certain assumptions about the nature of the world. These assumptions retain an element of arbitrariness enabling the practitioners to suppress ideas inconsistent with the paradigm. In effect, ‘normal science research is directed to the articulation of those phenomena and theories that the paradigm already supplies.’[1] The arbitrariness, however, also serves as a catapult for change once a given set of assumptions moves at least some practitioners to reevaluate their commitment to the assumptions.[2]

In his Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn tells us that scientists routinely operate within paradigms providing certain assumptions about the nature of the world. These assumptions retain an element of arbitrariness enabling the practitioners to suppress ideas inconsistent with the paradigm. In effect, ‘normal science research is directed to the articulation of those phenomena and theories that the paradigm already supplies.’[1] The arbitrariness, however, also serves as a catapult for change once a given set of assumptions moves at least some practitioners to reevaluate their commitment to the assumptions.[2]

The momentous episodes where a new set of commitments appear is what Kuhn calls scientific revolutions. These episodes necessitate ‘the community’s rejection of time-honored scientific theory in favor of another incompatible with it.’ They offer the opportunity to reframe at the level of metareality the change that takes place at the conceptual level. Since the assumptions of normal science are constructs of the mind to interpret reality and not a reality in itself, reframing allows us to renew our minds and look at reality differently.[3] ‘To reframe, then, means to change the conceptual and/or emotional setting or viewpoint in relation to which a situation is experienced and to place it in another frame which fits the ‘facts’ of the same concrete situation equally well or better, and thereby changes its entire meaning.’[4]

We are at the crossroads of a great opportunity to reframe the racial debate. A generation invested heavily in the paradigm of eternal victimhood is slowly fading not by the appropriation of a new paradigm but simply because of age. Most black intellectuals still cling to the old paradigm, unwilling or unable to shift. Yet, a new generation of blacks not stained by the scorch of segregation and more interested in universalism is emerging. The possibility of challenging the theory instead of simply elaborating on and reformulating it is real.[5]

Yes, ceasing to agree with the liberal radical consensus has its perils. As in normal science, to work under different premises is to cease to be a member of the community: ‘Work under the paradigm can be conducted in no other way, and to desert the paradigm is to cease practicing the science it defines.’ But we are no longer in the time when the entire spectrum of scholars operating outside of the paradigm consisted of two men, Thomas Sowell and Walter Williams. Their desertion, I submit, was the ‘pivot about which scientific revolutions turn.’[6] We are at the crossroads of the dawning of a new era where a growing sense that the existing ideologies of race and its messiahs cannot meet the needs of a community whose problems are precisely the result of an environment they created.[7]

‘Discovery commences with the awareness of anomaly, i.e., with the recognition that nature has somehow violated the paradigm-induced expectations that govern normal science.’[8] Sowell and Williams opened the eyes of a generation to the puzzling reality of the failure of the liberal/radical paradigm to effect real change. It is precisely the appearance of certain puzzles that creates the opportunity for qualitative leaps. As those operating within a given paradigm often insulate themselves from socially important problems not reducible to the assumptions of the system, they unwittingly open the opportunity to challenge the very assumptions giving life to normal science by the discovery of ‘pockets of apparent disorder.’[9] These pockets, unanswerable by the accepted assumptions, can provoke a scientific revolution.

‘Discovery commences with the awareness of anomaly, i.e., with the recognition that nature has somehow violated the paradigm-induced expectations that govern normal science.’[8] Sowell and Williams opened the eyes of a generation to the puzzling reality of the failure of the liberal/radical paradigm to effect real change. It is precisely the appearance of certain puzzles that creates the opportunity for qualitative leaps. As those operating within a given paradigm often insulate themselves from socially important problems not reducible to the assumptions of the system, they unwittingly open the opportunity to challenge the very assumptions giving life to normal science by the discovery of ‘pockets of apparent disorder.’[9] These pockets, unanswerable by the accepted assumptions, can provoke a scientific revolution.

Those operating within the model indeed assume a sense of authority over a set of rules they impose as binding on all. As these are, again, arbitrary and political, they cannot prevent some from not abiding by them. ‘Normal science can proceed without rules’ says Kuhn, ‘only so long as the relevant scientific community accepts without question the particular problem-solutions already achieved.’[10] Failure of the rules to explain reality and offer solutions is the necessary prelude to the search for new rules, new foundational assumptions.

Before us, we have three options. The first is to adhere to the old paradigm of victimhood and adopt its reactionary resistance. The second is to intellectually reject the old paradigm but accept its practical application by concluding that there are no real alternatives. That is the road already traveled. Then there is the possibility of the emergence of a new paradigm with new rules and new expectations. We dare to hope that the last alternative has already been conceived in the minds of a few such as Sowell and Williams who were from the start not committed to the fundamental assumptions of racialism. There is now an opportunity to renew our minds and finally see anew:

Led by a new paradigm, scientists adopt new instruments and look in new places. Even more important, during revolutions scientists see new and different things when looking with familiar instruments in places they have looked before. It is rather as if the professional community had been suddenly transported to another planet where familiar objects are seen in a different light and are joined by unfamiliar ones as well.[11]

[1] Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, p. 24. [2] Ibid, pp. 5-6. [3] See Watzlawick, et. al., Change, p. 97. [4] Ibid, p. 95. [5] Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, p. 33. [6] Ibid, p. 34. [7] Ibid, p. 92. [8] Ibid, p. 52. [9] Ibid, p. 42. [10] Ibid, p. 48. [11] Ibid, p. 111.