“For the sons of this world are shrewder in dealing with their own generation than the sons of the light.”

–Luke 16:8

The Civil Rights Movement grew out of a profound spiritual conviction that the men and women of that generation were called to ignite the fire of righteousness and truth. It seemed as if God had planned for a people of destiny and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was born in the midst of that calling. He was born in an era of social and legal injustice against blacks, and experienced it early. One day, as a child, he observed his father sit down in the front waiting seats reserved for whites. The shoe store clerk blurted, “If you will move to the back, I’ll be glad to help you.” Daddy King refused, the clerk refused to serve him, and Mr. King took little Martin out mumbling, “I don’t care how long I have to live with this thing, I’ll never accept it. I’ll fight it till I die. Nobody can make a slave out of you if you don’t think like a slave.”[1]

Daily reminders of his degraded state seemed to contradict what he was learning from his dad about human dignity. Why were blacks required to address whites, even children, as “Mr.” or “Mrs.” but all blacks were always called by their first names, even if they were elderly? The pain of insulting treatment was worse than what any law could deprive.

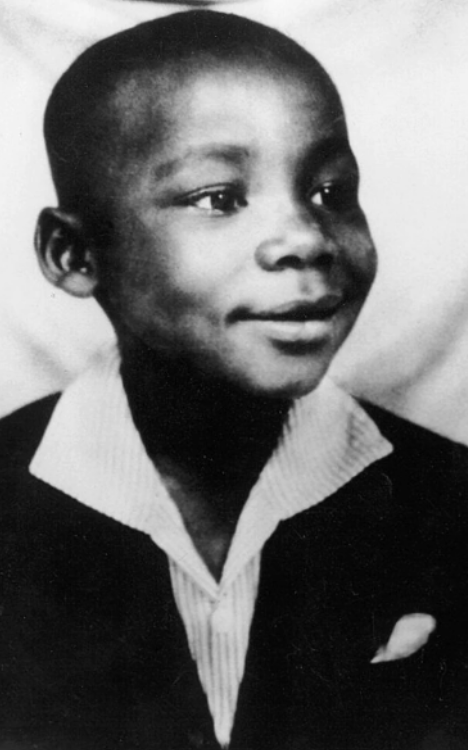

Photo Credit:Intellectual Properties Management, Inc., Licensor of the King Estate; AP

The church was the place where he could find affirmation, a second home for a spirit bewildered by acts of injustice that did not make sense. At Ebenezer Baptist Church he could be somebody among a community that affirmed him and saw blacks as having a high destiny that could not be taken away no matter what whites did. It was a haven where, even if only for a few hours, Martin could have a respite from those who hated him. That spirituality was planted in him and remained there for his whole life.

There was also an endeavor that inspired him: education. Words engulfed him in a world of possibilities. “You just wait and see, I’m going to get me some big words,”[2] he once told his parents. Education also served as a cleansing agent that exorcised the anger and resentment that builds up when you are mistreated. In college, he had the opportunity to work alongside whites who were fighting against racism, people of goodwill. “I was ready to resent the whole white race, but as I got to see more whites, my resentment softened and a spirit of cooperation took its place.”[3] At the same time, white stereotypes presenting blacks as degraded and unintelligent motivated him to excel, to show them they were wrong. Even when the possibilities seemed grim and the rules tilted to ensure his failure, he succeeded.

Although King embraced Protestant liberal theology, he was also influenced by natural law thinkers of traditional philosophy and the personalist school. He was not far away from Aquinas and Niebuhr. It is as if he was shaping a worldview, an interpretive lens tinted with all sorts of influences that eventually led to an integrationist approach where hope, informed by reason, led the way. Supported by the songs and the faith of Negro spirituality he began to see the transcendent light that left color behind and affirmed with Paul that “we are all one in Christ.” (Gal. 3:28) The black church also had a tradition of great respect for the pastor as a caudillo of destiny. King’s leadership was honed and his calling for a mission was formed. His studies finished, he returned to a different scenario than the intermittently welcoming one in college; he went back to Montgomery, the “Cradle of the Confederacy.” By the time that Rosa Parks had enough, King was ready.

This destiny was joined by many others whose cradle was the black church and whose aim was also hope. They were able to see beyond the degradations of everyday life, embrace a set of truths about the human person, and recognize them in the founding values of the nation. A cry began to build, a cry for justice. “Be true to what you say on paper!” They indeed embraced that meaning of the papyri better than anyone else in the nation. Even as white clergy remained unmoved, there were these prickly truths that mobilized and eventually transformed the nation. There was a price to pay for rocking the boat. King’s universalism did not fade even as most of those who preached it cowered under pressure. The black church embraced the movement and the name of King’s organization reflected its religious roots: Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Its mission was “to redeem the soul of America.”

It was that redemptive essence that informed the movement as it challenged America and engaged in an arduous, and unprecedented effort, one that called blacks to pick up a cross. But that cross changed America. It became a movement based on a universal faith in humanity, a courageous insistence on non-violence even when it seemed ineffective, and an embrace of the values of the founding as these for the most part reflected the natural law of God. It was integrationist, personalist, and hopeful.

There was, however a great, challenge ahead—a challenge brewing from within the bosom of the movement and whose antecedents were not aligned with King’s. It was not Christian but secular. It was not hopeful but hopeless. It was not reformist but revolutionary. It was not seeking reconciliation but power.

That movement will be discussed in a subsequent article.

[1] Martin Luther King Jr., Stride Toward Freedom (New York: Harper & Row, 1958) p. 19.

[2] James H. Cone, Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare (New York: Orbis Books, 1992) p. 26.

[3] Stephen B. Oates, Let the Trumpet Sound: The Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Mentor Books, 1985) p. 17.