There is a monumental fault line dividing people in America (and many other places). The two sides aren’t black and white, Christian and atheist, or liberal and conservative. They are barbarism and civilization.

For ancient Greeks and Romans, the “barbarian” was a foreigner—a German or Briton or African who did not share the culture of law, philosophy, technology, and religion that characterized those Mediterranean empires. Gradually, however, the term came to apply less to ethnic or national boundaries and more to education and etiquette. Those who were trained in and accepted the dominant customs, manners, and mores of society could be considered “civilized”; those who rejected those norms in one way or another behaved “barbarically.”

In our current casual and egalitarian age, when behaviors such as coarse language and sloppy dress no longer disqualify one from respectable society, the very idea of distinguishing between civilized and barbarian strikes many as offensive. But the distinction ought to be rehabilitated in the present climate, even if its meaning has shifted. For one of the marks of civilization is the gathering of people in cities (civitas in Latin), where they participate freely and peacefully in politics and commerce. This requires adherence to a rule of law regarding respect for property persons.

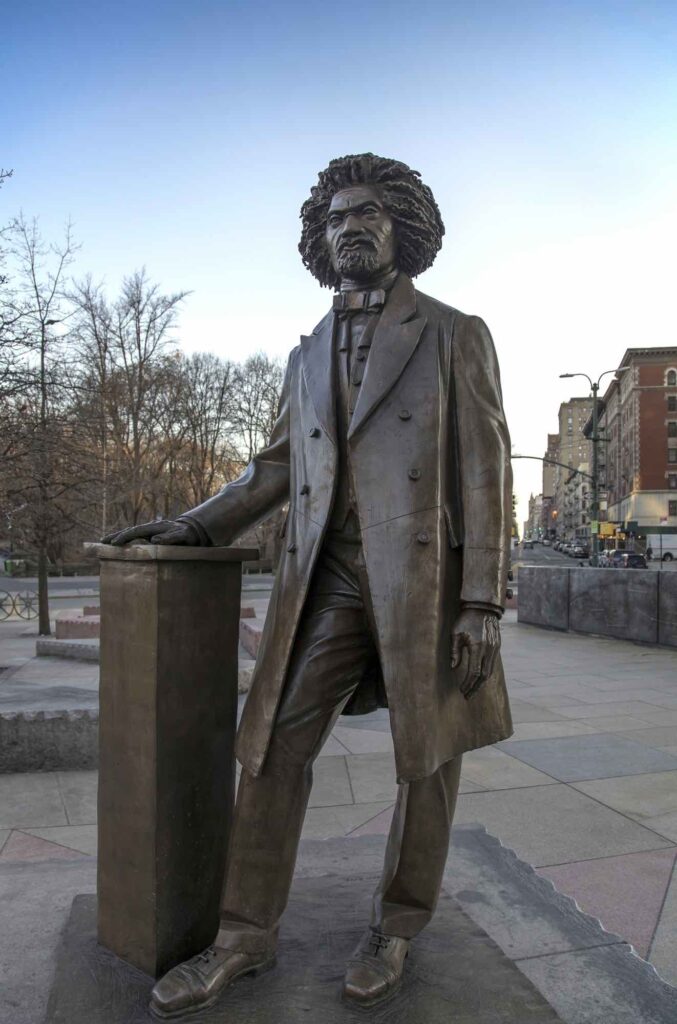

Unfortunately, the widespread lack of such respect is increasingly evident. Among legions of examples from recent weeks that could be cited are the violence within the “CHOP” in Seattle; the destructive rioting in Minneapolis and many other cities; and the vandalism against statues of heroic figures in American history, including Junipero Serra and Ulysses Grant in California, and Frederick Douglass in New York. This barbarism is not unique to the political left or the political right; it can be found wherever confrontation with difference erupts into shouting, shoving, or shooting. It can be found among politicians, police officers, and pastors, as well as activists, anarchists, and adolescents of all ages. As the Reverend Dean Nelson of the Frederick Douglass Foundation said in the wake of the Douglass statue incident, “There are people within our culture that are more committed to creating chaos then they are solving problems and finding solutions.”

The widespread nature of these instances of mob rule and violence is one marker of the rise of barbarism. An even more distressing one is the unwillingness of broad swaths of the American elite to condemn them unequivocally. In some cities, mayors and other officials have given free rein to property destruction and even assault.

Without question, there are among us wide and deep differences of position and opinion on crucial matters of politics, religion, and morality. We don’t agree on how to combat poverty or racism or disease. But in the midst of such diversity there are only two options: Working through differences in the context of fundamental agreement on the standards of conduct and debate and adjudicating them through fair and consistent political processes; or settling them by force and violence according to the principle of “might makes right.”

This is a deeply ironic moment. Most of the progress the world has made with respect to the treatment of ethnic and racial minorities, women, and other out-of-favor or out-of-power groups, has come about precisely because appeals to sound moral principles have triumphed over “might makes right.” Those who, in the name of social justice, are fomenting a turn to violent settlement of disputes are playing a dangerous game, one that will ultimately result in regress in the quest for justice and equality.

Unless we can agree on the unexceptionable tenets of respect for other human beings and law and order, the common pursuit of other aims can never even start. We must all choose, right now, and stick to our choice no matter how inflamed our passions over any injustice or abuse: Civilization or barbarism?