Creating a new nation by severing connections with the past was the founders’ generation’s remarkable effort. By bringing together from afar various peoples, they were attempting to interweave threads historically deemed incompatible with social cohesion. Nation-states were previously created by homogeneous populations through many generations of common existence. Ethnic identity was crucial for the building of national identities.

The Americans, however, endeavored a curious experiment whose end was creating a union that despite ancestral disparities was to weave around a set of universal principles. Distilling into a common vision, a variated multitude was to become a unified whole. E pluribus unum. Writing in his journal, the great essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson called that America was destined to become “asylum of all nations, the energy of Irish, Germans, Swedes, Poles, and Cossacks, and all the European tribes ─ of the Africans and of the Polynesians, will construct a new race… as vigorous as the new Europe which came out of the melting pot of the Dark Ages.”[2] George Washington spoke of a home “open…to the oppressed and persecuted of all Nations and religions.”[3] It is rather apparent that Washington was not referring only to white Christians.

“We have it in our power to begin the world again” ―Thomas Paine[1]

Similarly, John Quincy Adams invited the multitudes to come to our shores to build a futuristic polity—more than a nation, a new world. He once baffled Baron von Furstenwaerther when in a letter Adams added the caveat that to become an American a German had to cease to be one. “They must cast off the European skin, never to resume it. They must look forward to their posterity rather than backward to their ancestors.”[4]

A Frenchman among us saw the struggle of creating one people from a “promiscuous breed.”[5] Astonished and delighted by what he saw in America, his letter back to friends in France exclaimed, “Imagine, my dear friend, if you can, a society formed of all the nations of the world … people having different languages, beliefs, opinions: in a word, a society without roots, without memories, without prejudices, without routines, without common ideas, without character and yet a hundred times happier than our own.”[6]

In his effusive praise that may have reflected hope more than fact, Tocqueville described a quest never before attempted but seemingly moving forward. There was no originating purpose of racial supremacy in the effort to build our nation. All the founders had was a desire to start the world anew, no matter the daunting challenges, by leaving behind old prejudices coming from an old way of looking at reality and instead affirming natural rights lived out in new ways. They were creating a society that depends on intermediary institutions between the individual and the state and, at the same time, telling everyone to mind their own business. It was in the messy midst of such revolutionary ideas that prejudice and human fallibility put up a fight to derail the glorious experiment. Or are we to imagine that the timber of frail human character was not to resist? Why would we expect that the conflict between ancient prejudices and a vigorous leap forward was not also reflected within individuals’ own hearts?

-

Gunnar Myrdal -

James Bryce

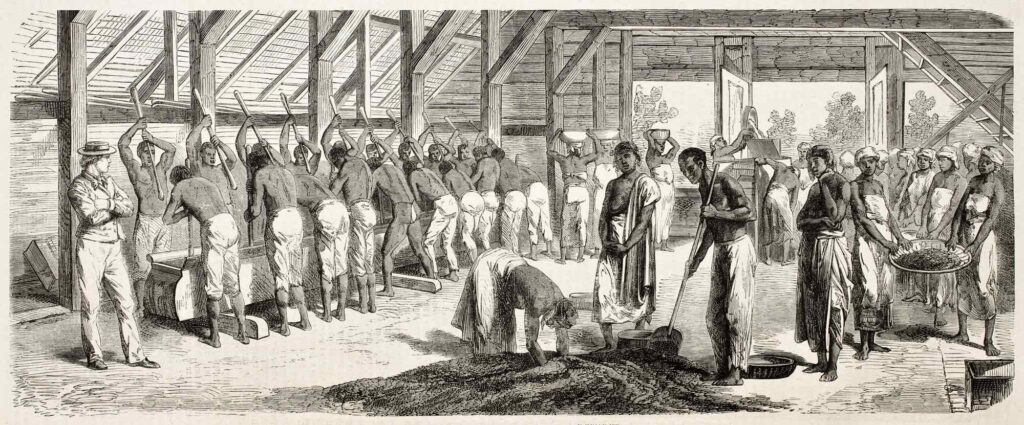

It seems rather obvious to me that the arrival at our shores of vile slave ships in 1619 cannot in any fashion represent the founding of our nation because slavery belongs to the ancient and ghastly realities of an old realm that affirmed the types of differences the American experiment was rejecting, albeit through a struggle with a world that refused to fade. It is evident that Crevecoeur first, then Tocqueville, and later men like James Bryce and Gunnar Myrdal, did not have the African slave primarily in mind when reporting on the building of an American character that seemed to be, in the words of Bryce, “quickly dissolving and assimilating the foreign bodies that are poured into her mass.”[7] Yet, the solvent of a new world with new values and new hopes and possibilities was active even in the lives of those suffering the cruelest degradations.

Yes, slavery and racial prejudice toward a rather uniquely different people were unity’s greatest foes. But the quest to vanquish them gave us something amazing, forged in fire: the black American, the quintessential American. No one more than Africans had to give up any hope of rejoining ancestral kinfolk and ways of living; no one more than they had to endure hardships; no one more than they had to overcome such centrifugal forces: first, internal divisions among slaves—as African tribal rivalries and variations were real—and, then, to unite with the other Americans, pale and threatening. But they did! They ceased to be Africans and became Americans in spite of the brutal force of the enslaver’s blade. And today we are not, in any fashion, Africans in the diaspora. We are home.

I marvel at them, these forebears, with amazement. When despair made sense, they hoped. When pain abounded, they sang. When frustration and hard labor threatened their very lives, they moved forward with quiet pride, with resilient determination. No one deserves the title of American more.

Tocqueville was incomplete in his description of how Americans became Americans, through civic participation and the exercise of political rights. There was a group of people who were deprived of those options and yet became Americans through sweat, blood, and tears—refining elements, martyred victory.

That martyred victory is at risk today, not primarily from racist forces still at battle with the glorious experiment in creating a new world but from a radically new understanding of America that tries to sever African Americans from their true identity and bow down to foreign ideologies arising from a foreign vision of the human person. They insist that blacks are not quintessential Americans but eternal victims, who do not belong and will be rescued, of all people, by the thought of a bourgeois German who was born in 1818.

[1] Thomas Paine, Thomas, Common Sense, 23.

[1] Porte, Joel, Emerson in His Journals (Cambridge, 1982) cited in Schlesinger, Arthur, The Disuniting of America (New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 1992) p. 24.

[2] J.C. Fitzpatrick, ed., Writings (Washington, 1938), xxvii, 252.

[3] In Werner Sollors, Beyond Ethnicity (New York, 1986), 4.

[4] The apt phrase comes from J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur’s Letters from an American Farmer, first published in 1782, a work in some ways considered a precursor to Tocqueville’s Democracy in America.

[5] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, vol. 1 (1836) chap. xiv.

[6] James Bryce, The American Commonwealth, vol. 2 (London, 1888), 709, 328. Cited in Arthur Schlesinger, The Disuniting of America (New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 1992), 26.