As the financial capital markets gradually recover from their pandemic-induced weakness, equal attention should be focused on the recovery of another kind of capital. Social capital—the capacity of people to cooperate toward common ends—has long been faltering and concerted effort will be necessary to shore it up.

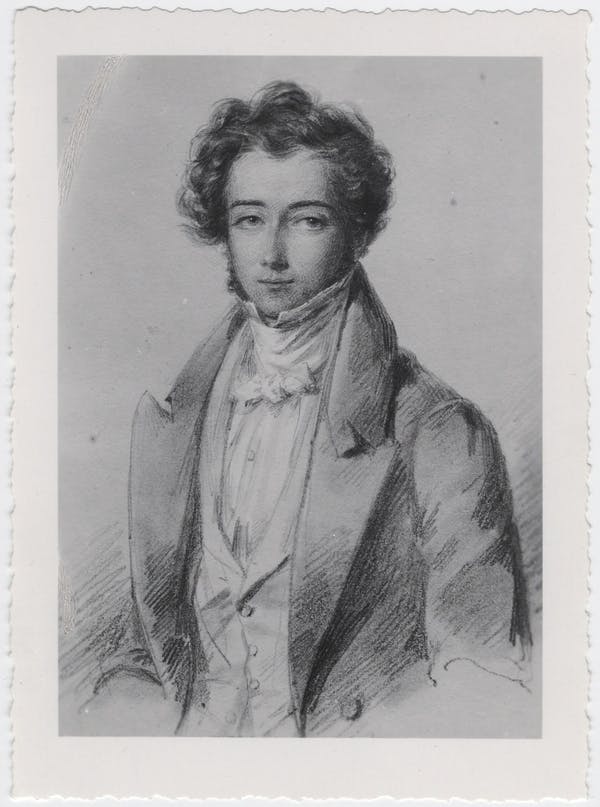

Although the term only came into common usage in the 1990s, the concept of social capital has a long history. When the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States in the 1830s, he was astounded by the level of social capital. “Americans of all ages, all conditions, and all dispositions constantly form associations,” he wrote. “They have not only commercial and manufacturing companies, in which all take part, but associations of a thousand other kinds, religious, moral, serious, futile, general or restricted, enormous or diminutive.” Tocqueville observed that, whereas projects aimed at the common good tended to be organized in France by government and in England by the elite, in America people from every background and status contributed to the general welfare. “I have often admired,” he reflected, “the extreme skill with which the inhabitants of the United States succeed in proposing a common object for the exertions of a great many men and in inducing them voluntarily to pursue it.”

This characteristic of American life, he went on to say, was especially important in a democratic society, because otherwise individuals would be powerless to accomplish projects and tackle problems confronting communities. Lacking the individual wealth or political power of European aristocracy, Americans were reliant on the ability to link up with others in the tasks necessary to create a flourishing nation.

There is ample evidence that this capacity—social capital—has been declining in the United States for some time. The Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam has been writing about it for some time: His 2000 Book, Bowling Alone, captures the idea in its title and his subsequent work has added to his case. Americans, he demonstrates, used to participate in associations—such as bowling leagues, labor unions, parent-teacher associations, and countless others—in high numbers; now they “bowl alone.”

Why this happened and how to restore social capital remain unsettled questions, but there are a lot of theories. One important factor is doubtless the decline of functional family life. As the first and most effective training ground for the virtues of social cooperation, the family is an indispensable generator of social capital.

Without strong families, children tend to grow up without one key element in the production of social capital: a sense of belonging. The Marriage and Family Research Institute has created an Index of Belonging to measure this critical ingredient of social life. Using 2008 numbers, it found that only 45 percent of American teenagers had “spent their childhood with an intact family, with both their birth mother and their biological father legally married to one another since before or around the time of the teenager’s birth.” Levels of belonging and rejection also differed substantially across regions, localities, and ethnic and racial groups. The breakdown of family life, initiated by the rejection of parents by each other, destroys the stable emotional environment within which children experience a sense of belonging.

This failure has massive ripple effects. In a forthcoming study, economists Barry and Maryann Keating describe social capital as “the capabilities embodied in individuals and employed by choice or habit to benefit society as a whole. In this sense, social capital is a subset of human capital, not merely an amorphous substance floating around in the atmosphere of certain communities.” In other words, even though social capital is naturally created in properly functioning communities, it is not automatic. It also requires the cooperation of people who are other-centered rather than narcissistic. “Conventional human capital—education and skills—can be acquired independently from cooperative skills,” the Keatings write. “However, to maintain the present stock of social capital, groups of individuals must choose to participate and accept the norms, disciplines, and objectives of particular autonomous organizations.”

There is no better place to learn to “accept norms, disciplines, and objectives” of an association of individuals than in a family. In fact, it is extraordinarily difficult to learn this at all without the formation that takes place in the home. Thus, any long-term and comprehensive solution to the problem of social capital must include a renewal of family life.

Even so, we must also do our best to improve our “social capital stock,” no matter the overall state of the family. This will involve recreating the role of the family within other institutions. Returning to Tocqueville’s and Putnam’s associational society is one good strategy. Participate in political organizations, yes, but even more importantly participate in non-political associations. Join athletic leagues, hobby groups, religious societies, and charitable organizations. Learn to commit to a goal, to cooperate and compromise with others who may have different views, to subordinate individual preferences and whims to the good of the group.

Nearly two hundred years ago, Tocqueville warned of the consequences of declining social capital. If people living in democratic societies “never acquired the habit of forming associations in ordinary life,” he predicted, “civilization itself would be endangered.” A people that lacked the wherewithal to achieve great things by “united exertions,” he concluded, “would soon relapse into barbarism.”