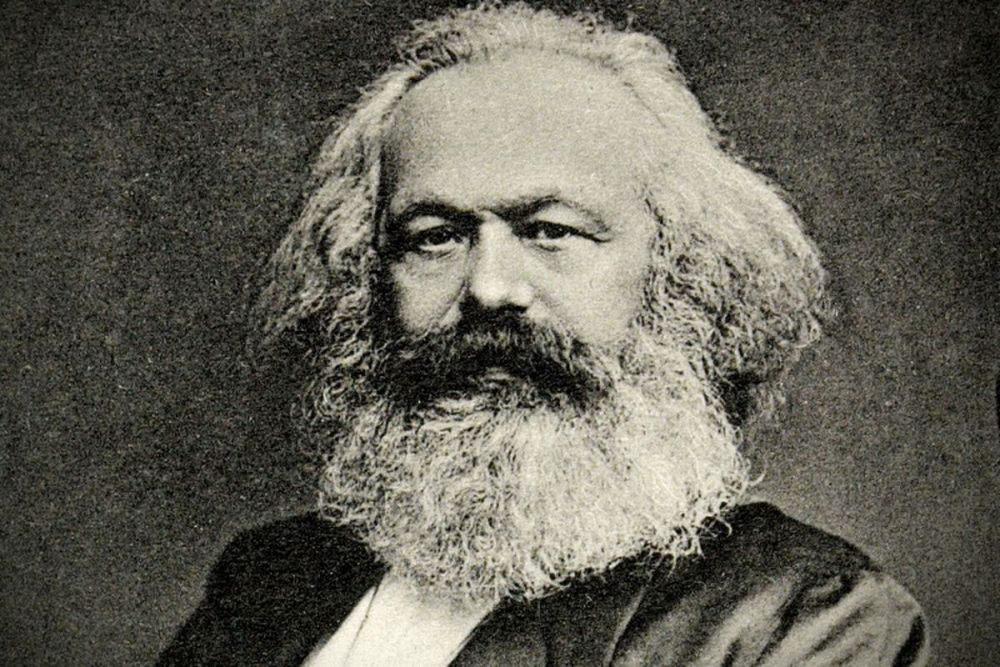

Labor Day celebrations are coming. We celebrate the worker and the creations of his hands. This wonderful celebration, however, has for long been informed by serious economic errors. The day evokes in me memories of marches I attended as a child, and the slogan we chanted, “Workers of the world, unite!” The famous rallying cry comes from The Communist Manifesto and was popularized in English as “Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!” The essence of the slogan is that members of the working classes throughout the world should cooperate to defeat capitalism and achieve victory in the class conflict. Karl Marx made the worker a hero. But who was Marx?

The man was born in 1818 in the city of Trier, Germany, during the period of the Restoration in Europe—the attempt at turning back the clock from the changes emanating from the French Revolution. His father was a secularized German Jew. When Marx was six years old, his father, for purely socio-economic reasons, converted to Lutheranism. Marx was then baptized as a Lutheran but by his fourteenth birthday declared himself an atheist. Over time, he became quite anti-Semitic. Eventually, he studied law at the University of Bonn, though he preferred history and philosophy. From Bonn, he moved to the prestigious university in Berlin around the year 1834, just a few years after the death of the great philosopher Georg Wilhelm Hegel. Eventually, Marx married a Prussian aristocrat, Jennifer von Westphalen.

Hegel’s influence at the University of Berlin was considerable even after his death. At the university, there were two competing groups of young Hegelians who differed in their interpretation of the philosopher. One group was on the left, (Linkshegelianers), and the other on the right. Those on the right were Christian idealists philosophically and the ones on the left were agnostic materialists. Those on the right defended the Prussian state but those on the left rejected it. Marx joined those on the left. This period of his life is characterized by his attempt at offering a response to the various interpretations of Hegel.

There are three important intellectual currents that influenced Marx during these and coming formative years, which Marx mentions in his writings that historians have characterized as “The Young Marx.” The first current was the thought of another great German Hegelian, Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach, a philosopher and anthropologist who interpreted Hegel’s metaphysics and provided a critique of Hegel’s doctrine of religion and the state. Marx read Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity, which portrays religion in general and Christianity specifically as false, a great error based on the human desire to create a god after man’s own image. The concept of God is where men deposit their hopes, fears, and unfulfilled expectations for eternal life, happiness, good health, and freedom. Man imagines a being after man’s expectations. What is important is mater, not spirit. After reading Feuerbach, Marx was still a liberal but now also a serious materialist.

The great Hegel was, of course, the other German philosophical influence on Marx, especially through Hegel’s dialectical logic. Three of his books were especially important to Marx: The Phenomenology of the Spirit, The Science of Logic, and the Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences.

In the first, Hegel develops his dialectic. He says that all men are in conflict with other men to gain power and control over nature. In turn, men want other men to respect their ownership over nature, transformed into property through their work. Those who take greater risks initially win over the less motivated in the competition to control nature and possess it. From that competition emerge owners (risk-takers) and slaves (the losers). The owners are saved from the dangers of struggling with nature and end up living in comfort out of the labor of the workers, the slaves who continue to struggle with nature. The slaves work and the owners enjoy the fruit of that labor.

However, the slave, having to tangle with nature, learns its secrets and places his ideas (his rational order) in nature. What the slave produces remains, but the owner only destroys, consuming the fruits of the labor of the slave. All of this seems to have a profound grain of truth. Easy riches are a curse, not a blessing!

A second concept that Marx takes from Hegel is the idea of alienation. Marx was attracted to the concept due to his own life as a Jew in a Christian world, later a Lutheran in a Catholic region, an atheist in a theistic world, and a bourgeois who wanted to be a proletarian. In the competition between owner and slave there arises, over time, a set of norms and institutions—credit, contracts, money, justice systems, social mores, banks, family life—that gain a life of their own and become in a sense foreign to man’s existence. As these are foreign, they oppress men and detach men from each other and from society—that is alienation. Thus, Hegel contributes to Marx the concepts of the dialectic and of alienation, both crucial to his theories.

After Marx was expelled from Germany in 1845 due to his political activities, he went to Paris. An important event in his life while in France was meeting the man who would become his best friend and collaborator until his death, Friedrich Engels. In France we can find another influence on Marx, which is the Parisian socialism of men such as Proudhon and Saint-Simon. This might be his first serious exploration of socialism. During this period, Marx was developing his theories. The year of his explusion, Marx published The German Ideology, co-written with Engels, where we see Marx beginning to develop his theory of history.

Marx got into political trouble again and was expelled one more time, landing in Brussels, Belgium. There, Marx, now joined by Engels, came into contact with the labor movement. One group of workers, known as the League of the Just, asked him to write a manifesto about his ideals, which he did in February of 1848. This is what we all know today as The Communist Manifesto. The manifesto was profoundly influential among Belgian workers, and Marx was expelled yet again.

London was his next destination and the setting for another great influence. The capitalist system was forming there and that movement, with its practical and theoretical influences, has a massive impact on Marx. England was then the only truly industrialized country in the world, a place with a booming economy, full of possibilities, and seeming contradictions and tensions.

Another often forgotten influence on Marx was the historical interpretation of the French Revolution by Jules Michelet, who in 1867 finished the great work of his life, Histoire de France, in nineteen volumes. There Michelet emphasized that one of the crucial outcomes of the Revolution was that a social class, that of the nobles and clergy, had been displaced by a new class, the bourgeoisie. The concept of social class as the key economic grouping in the dialectic was an influence coming from Michelet.

The third important intellectual current was the English contribution in the economics of men like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, James Mill and his son John Stewart, and others. What could these classical liberals possibly contribute to Marx? Probably the most important element is the value of human work, but he also learned about the other two factors of production: land and capital. Specifically, for example, from David Ricardo Marx took the subsistence theory of wages, also known as the “iron law” of wages. According to the “iron law” theory, wage levels tend to fluctuate around the minimum necessary for providing the means of existence. (The classical liberals made their mistakes and these were later corrected by other contributions, such as the role of the entrepreneur and the concept of marginal utility.)

These are the three great influences on Marx: German philosophy, French socialism, and English economics. A fourth might be said to be the Belgian workers movement. These influences converged in him, a genius of his time who was able to synthesize these currents of thought into a powerful, although ultimately destructive and evil, political ideology and revolutionary world movement.

Marx was however seriously wrong in his historiography and his economics. It is possible, as Hayek points out, that, being intellectually honest, Marx delayed the publication of the second and third volumes of Das Kapital because he was unable to offer a serious response to the classical theory of marginal value developed by Menger and others. The marginal theory of value is the subjective theory of value which is basic to all the theories of the Austrian School of Economics. It can be argued that as a serious school of economics, Marxism died by 1870—and yet, its effects remain with us. The story of how Marginalism destroyed Marxism will be for another time.