The trans-Saharan slave trade dates to the second century AD, and fully functioning slave markets abounded for centuries in various parts of the world. However, slavery largely had died out in Europe until its resurgence during the era of discovery and colonization that saw the Portuguese establish the first Atlantic sugar plantations in the Madeiras (1455) and the Canary Islands (1496). The labor system instituted in those places served as a model for the New World’s sugar plantation system. Brazil was the first transatlantic destination for African slaves, who arrived there in 1538, and later the despicable slave ship brought 350 slaves to Jamestown in 1619.

Much has been said about that dreadful event in Jamestown. If we attempt to understand the struggles of race in America from that date on, we must look not only at the antecedent factors often lying just beneath the surface of these events but also at the narratives within which they are embedded. These narratives, or filters, are often presented as conferring epistemic privilege for some and epistemic blinders for others. For that reason, it is important to understand these constructs. There are, in my estimation, two major narratives of race that ought to claim our attention.

Race in History

Before we examine these two narratives, let us quickly glance at the larger question of race in history. The very concept of race seems to be a fuzzy category, lacking clear biological classification. Race as a biological phenomenon is subjective and does not represent a definite category in nature. Instead, race exists as part of a continuum with arbitrary boundaries that are socially construed. As Thomas Sowell states, “If race were conceived of in purely biological terms, it would be a concept that could be applied to only a relatively handful of people on a few small isolated islands in the oceans. … What are called ‘races’ in this context are simply groups of people with substantially differing proportions of genes from various racial stocks.”

Starting in the early part of the 17th century, several developments occurred that generated the modern concept of race. Among these factors was Western exploration, ignited in part by mercantilism and the discovery and colonization of new peoples, which brought cultures closer together and made human differences more apparent. The popularization of Darwinism, along with the related though distinct emergence of the theory of Social Darwinism later in the 19nth century, is another important factor. Darwinists were the first to attempt to bestow on racism some semblance of scientific validity. It is interesting that the subtitle of Darwin’s “On the Origin of the Species” (1859) was “The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.”

With these influences and the human propensity to parochialism, it was to be expected that people sought answers in a theory of race to questions such as why certain people possess what seem to be inferior cultures. Of course, inferiority is in the eye of the beholder, and the aforementioned parochialism tends to lead us to place ourselves at the pinnacle of civilization. In fact, anthropologists have shown that some of the most primitive tribes embraced myths that placed their tiny groups at the center of the universe.

With the Darwinist insistence on a hierarchy of survival enthroned as a tenet of science, the ideological framework was in place for a rationalization of racial domination. If the question of who is “superior” is asked, the questioner often will find an obvious answer: “Well, we are, of course!” Classifications came with a vengeance under Darwinian influence. Think about it: the age of exploration, mercantilism, trade, Darwinism. All these gave a new twist of justification to an ancient institution: slavery. Rivalries among the European powers created a voracious appetite for cash crops and new sources of precious materials, and the need for manpower to harvest the bounty. There was powerful demand for a theoretical justification for chattel slavery.

As we know, slavery was ancient and universal. Sociologist Orlando Patterson tells us that “slaveholding and trading existed among the earliest and most primitive of peoples. The archaeological evidence reveals that slaves were among the first items of trade within, and between, the primitive Germans and Celts, and the institution was an established part of life.” Virtually as ancient as civilization itself, slavery existed in Africa, China, Japan and the prehistoric Near East. Hunter-gatherers in North America practiced it. The North American Cherokees practiced slavery, with slaves being the “atsi nahsa’i,” or people without rights or participation in social life. Their main purpose was to serve as an anomaly, pointing to the strength and unity of the Cherokees as a group.

However, in Europe there was another important influence: Christianity. Under the influence of religious groups such as the Quakers, by the end of the 18th century slavery seemed intolerable, and in 1807 Great Britain abolished its slave trade. Fifteen years later, France followed suit. Eventually the Christian West not only questioned slavery but birthed a movement to end it. These accomplishments occurred despite strong opposition from most of the non-Western world. African tribal leaders in Gambia, Congo and Dahomey (Nigeria) sent delegations to London and Paris to lobby against ending the slave trade, and intra-African trade in slaves grew exponentially after the Europeans ended their participation.

The quest to abolish slavery extended to America, although it took longer to achieve here, mostly because of economic reasons. The antebellum South evolved into a segmented economy heavily dependent on agriculture, with an aristocratic elite benefiting from slave labor. It is important to note that blacks were not enslaved because of Darwinian biological theories; they were enslaved for economic reasons. Slavery later was rationalized using various theories, including the Darwinian, which became prevalent only after the paternalistic religious rationalization began to falter. Because slavery in many places had become a racialized institution, theories of racial superiority were invented to justify its continuation. Thus, even after slavery was legally outlawed, those theories were still potent weapons of justification for efforts to maintain the economic and political dominance of some races over others. This explains why Darwinism, which emerged only as systematic slavery was in its death throes, remained a vital component of racialist thought.

In any event, our history was imbued with a binary reality: a country founded on the idea of freedom still had within itself a racialized institution that contradicted the goals of liberty. With this background in place, we can now discuss the two streams or narratives of thought used to explain the American race problem.

The Personalist Narrative

The first stream is one I call the Personalist/Integrationist Approach (PIA). It is important to note in addressing this stream of thought that America benefited from the idea of individual freedom as an institutional value, which only took hold in the Christian West. As sociologist Orlando Patterson tell us, “While the idea of freedom was certainly engendered wherever slavery existed, it never came to term. People everywhere, except in the West, resisted its gestation and institutionalization.”

In non-Western societies, and for a period also in the West, the slave dreamed of becoming socially “born again” by recapturing acceptable social dependency. That dependency was his only hope, because full citizenship after being released from slavery was seldom attained. Personal freedom as we understand it was denied not only to the slave but to all members of tribal societies; all relationships were dependent on the community. In effect, it is in the relationship between the slave and the “freeman” that we find the essence of the idea of freedom in the non-Western world — the freeman’s liberty consisting of full integration within the kin group rather than individual liberty. In the absence of the possibility of individual independence, there was a more practical goal for non-Westerners: that of fully belonging to the group for some and, for the slave, the reduction of marginality by regaining corporate status socially, legally and ritualistically.

This regaining of corporate status was to be accomplished by escaping or by attempting the often-unsuccessful task of being welcomed within the clan of the slave’s captors. There was social capital in being a member of the tribe, and often the slave was a kind of social currency and token of recognition of the value of integration, a reminder for the tribe that the members were not like the slave and that unity within the group brought about safety from the dreaded fate the slave exemplified. The free-slave dichotomy was not obtained in the non-Western world because all social status was involuntary and subordinated to the community.

In the PIA understanding of race that informed the earlier stages of the civil rights movement, the person, the individual, has a status different from what was conceived by the non-Western mind. Ethnic identity is seen as an aspect of the larger reality of individual personhood. Through a long and interesting historical process magnificently told by Orlando Patterson in his seminal book, “Freedom In the Making of Western Culture,” the Western mind conceived an alternative of social existence that was neither isolation and social death nor subordination to the group. Personal freedom was eventually conceived and actualized. A series of revolutions in ancient Athens transformed the Western world in a way that allowed for the social construction of freedom as a central value. This central value became a preoccupation for Greek philosophy, and later for the Christian natural law tradition via its connection to Aristotelian thought.

Roman power expanded this idea both in geographical terms, through conquest and rule, and in social terms, concerning who could aspire to it, as they co-opted the leadership of allied states. Through compromise and strategic maneuverings for power, freedom was indirectly expanded to others. Christianity, in effect, moved this journey toward its institutionalization. The possibility of autonomy against the threat of dreadful slavery obtained in this environment, whereas only fusion within the kin group emerged as a practical alternative in the non-Western world.

The Western mind thus arrived at autonomy through a long struggle that was in many ways parasitic to the very existence of slavery. Personalists believe that the Founders of our nation were, for the most part, successful in suffusing our founding documents with universal natural law principles of individual human dignity consistent with the Western development of the idea of individual freedom. Whatever one might think of the arrival of slaves in 1619, its significance is filtered through the prism of the understanding of freedom expressed in the documents of 1776 and the Western discovery of individual freedom. The existence of contradiction on the ground of experience is to be expected in a process that, as we have detailed, saw human beings at the crossroads of various influences.

Adherents to this stream believe that the American constitutional framework could, over time, overcome social, economic and political racial stratification and expand the realm of freedom. Embedded in the founding principles of the Constitution was the seed of the solution to the problem, even if that solution required a long and often arduous and painful journey. The Constitution was not perfect, but neither was it tragically flawed. Its basic principle was not white supremacy but liberty.

The 1960s civil rights movement was grounded in the belief that black integration was a right, a social good, and a real possibility. Just as Westerners over time discovered that the dichotomy of social death or collectivist integration was false because there was another option, the movement thrust ahead, albeit in the face of great struggle, by rejecting the social death or separation alternative. Dr. Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is probably the best expression of this view. “Be true to what you say on paper!” was his cry.

The antithesis to the slavery system brought to our shores as human cargo in 1619 was freedom in the Western sense: freedom to a group of people destined to recreate themselves in a foreign land that became their own — a people destined to be the quintessential Americans who forged an existential reality in the midst of isolation from their past and the imposed degradation of their present. Partial resocialization within the master’s community was not destiny but a step on a journey of full integration informed by the value of freedom. Reform is possible, however searing conditions might seem at a given time, if there is historical evidence that positive changes can occur based on the substantive set of principles that inform a system. The arrival of slave cargo ships in 1619 was the background against which the story of a people was forged, based on the principles of liberty carved in 1776. Slavery was scenery in the drama of a new people of destiny.

If this is true, the heart of the PIA understanding of race in America can be said to be optimism. This optimism is neither without justification nor without caution, knowing well that the emergence of freedom in history was never without travails. Optimism is possible because the philosophical foundations of the Constitution, benefiting from the long and arduous discovery of individual freedom in the Western mind, demonstrated that it is possible to expand its reach to cover more and more classes of people. In other words, this stream was integrationist, reformist and optimistic, while recognizing the reality of sin, and this aligns it with philosophical realism.

This optimism is complemented by the Christian expansion of salvation to the gentiles. The gentiles were called to the church and, as the church and the state drew closer and the power of Rome backed the church, liberties were expanded from the kin group to the nations. The very distortions of biblical exegesis used by some to justify enslavement demonstrates that in the Western and Christian mind there needed to be a way to accommodate action to biblical principles that pointed in the direction of freedom. There was a psychological and intellectual need to find a way to deal with the ideas of liberty found in biblical stories. Moreover, the adherents to this stream espoused the same conviction shared by John Adams and many other Founders: that general, immutable and unalterable Christian and natural law principles informed the meaning of law in the American constitutional understanding of governance.

As Martin Luther King often repeated, a law lacks character as true law when it is unjust and violates the eternal moral law, and it must be disobeyed precisely because it violates the principles of the Constitution. His philosophy was deeply personalist. Natural law is a finite reflection of the infinite wisdom of God and human law must conform with this reflection. In a sense, natural law gives this stream of thought an adherence to universal truths about the human person as a point of departure to understand social reality. The human person, unique and unrepeatable, with the moral capacities of reason and volition, stands sui generis in the midst of the group, whose wellbeing does not supersede the dignity embedded in the person but which is called to respect that dignity in view of the common good.

Christian doctrine and natural law principles of the primacy of reason were thus indispensable elements in the development of American constitutionalism. Adherents to the PIA stream embraced these Christian principles as they started a movement that altered the face of America. As tempted as they were to succumb to pessimism altogether, they remained aligned with the stream built on hope and optimism. Martin Luther King’s life serves as an icon of such commitment. In the face of constant criticism, he stood on the principles of the founders, even though some might question why. In his final “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, in which he sees himself in the shoes of Moses (Numbers 27:12; Deuteronomy 34), King said, “He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain and I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!” He was killed by an assassin’s bullet the very next day.

The Dialectical Narrative

The second understanding of race relations is the Dialectical/Separationist Approach (DSA). The dialectical approach sees human universalism as an aspiration instead of a point of departure. Universalism is obscured by oppression; thus, talk of universalism tends to ignore questions of justice. The DSA stream follows the vision of freedom affirmed by the non-Western mind, where freedom is realized only by full integration within the kin group and by the individual’s conformity to the will and ultimate goals of the group. Each person is a drop within the great wave of ethnic belonging and, if faithful to the collective, that drop gains meaning. The point of departure is not the individual person, unique and unrepeatable, standing sui generis, but the group. Individual freedom is sacrificed at the altar of what Patterson calls “sovereignal freedom.” Sovereign freedom relieves the individual from isolation in exchange for loyal service, deference and loyalty to the group. It is within the group that freedom is found, collectivized for the sake of survival. Conformity to the role, expectations and culture of the group offers a necessary safety that prevents alienation into the nothingness of individuality.

The pull of such a conception is powerful because, in the context of slavery, commonality as a method was crucial for survival in the face of brutality. It is also luring because it is deterministic. If “the system” is the culprit for the lack of personal autonomy, there is a good reason to affirm that condition as part of one’s identity. If being an individual black person is a persistent woe informed by pitiless despair, and there is no expectation of reward for one’s accomplishments, a collectivist explanation arrives almost by necessity. A given racial group is guilty (and their society instrumentally at fault) and another racial group is a haven of security, affirmation, contingency and counterattack. In the face of self-doubt manufactured by the oppressor, groupthink seems a good place to relieve one’s vulnerability, just as the non-Western tribal member saw in the kin group the practical solution to the perennial threat of enslavement and social death. In this view, individual freedom as the matrix for understanding black aspirations is an impediment to finding solutions, as it is as practically impossible today as it was practically impossible for tribesmen in the prehistoric savannas of Africa.

There is a real tension here as two civilizations and modes of understanding — the enslaver’s and the enslaved — merged in the context of antagonism. Leading leftist scholars such as Derrick Bell reflect a dialectic of antagonism as they tell us the founding itself was the problem, as the Founders betrayed the ideals to which they gave lip service. The normal science of this stream of thought has become the assertion that there were no values to adhere to that could serve as the link between those brought here in chains and the hope for eventual integration. In this view, an oppositional stance is the only way to affirm authentic love for the group, and blacks at best could only aspire to become the “enemy within” American society. Just as slaves did among non-Western tribes such as the Tupimamba of the Amazon, blacks might find a temporary place within the foreigners’ group but their destiny was social and physical death and their daily experience a combination of fear and contempt. As Patterson explains, “Commitment to the autonomy and strength of the group often entails a submission of one’s identity to that of the group. Collective freedom, collective power, and collective responsibility are all bought at the expense of the individual’s complete suspension of, or submission to, the will of the group and its leaders.”

Malcolm X is probably the best-known exemplar of the separationist and dialectical stream of thought, which sees the black American experience as a “nightmare” and finds inspirational antecedents in the slave rebellion spearheaded by Nathanial “Nat” Turner (1800–1831) and the black nationalism and Pan Africanism of Marcus Garvey and the Nation of Islam. In the 1960s, Stokely Carmichael and Willie Ricks popularized the “Black Power” slogan. Both were active in the Black Power movement as it became the socio-political arm of the dialectical stream, which served as a counterbalance to the personalist stream by the latter part of the 1960s civil rights movement. Following the 1965 Watts riots in Los Angeles, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committeesevered ties with the mainstream civil rights movement.

This separation is an early hint of the ultimate clash between the personalist and dialectical streams. The more radical civil rights movement militants argued for the need to build power through forceful militancy that will allow for an eventual separation, instead of seeking integration through accommodation within the system called America. In a similar vein and during the same period, Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party.

As this stream’s narrative goes, America is a criminal enterprise that has forced blacks into poverty, drug addiction, degradation and crime, and only a dialectical severance from the essence of America, whether by radical alteration of its structures or actual physical (geographical) separation, is sovereignal freedom to be attained. The key to Western success and the essence of the American founding are not freedom but oppression: specifically, the crimes of ethnocentrism, colonialism, imperialism and racism. And the key to ending this oppressive and irreformable system is power.

This understanding of race relations emphasizes collective identity, collective innocence, collective guilt, and collective and separate destiny. Race and the kin group become a basic reality, a sort of practical absolute, the heart of identity (racialist essentialism). Remarkably, we might add, the way this system reads American history is exactly the same way the infamous Chief Justice Roger Taney of the Dred Scott case and the rabid racists read history. The ground of understanding of the dialectical system is akin to the non-Western view of freedom and fully aligns with Marxist dialectical materialism and Marxist analysis of history.

Instead of class moving history forward, race is the catalyst. A racial “brotherhood” and the concept of self-determination acquire a similar meaning to that of Marxist class consciousness, where the self is the racial group. For Marx, class consciousness is a phenomenon born out of historical collective struggle, which brings to bear objective features that must be shared by members of the group. Similarly, racial self-determination in this stream refers not to the fate of individuals who share an ancestry but the collective fate of those who share an ideology. The antithesis of class consciousness is false consciousness, and that false consciousness, when applied to the racial group, refers to individual members of the kin group who deviate from what is generally understood as the interests of the group vis-à-vis its oppressor. Again, individual freedom and integration become the enemies of the separatist and dialectical stream. Collective self-determination is not seen instrumentally as the context within which individual responsibility is appropriated and individual freedom enhanced; instead, the ultimate goal is fusion of the self with group consciousness.

As collective identity is the mark for both the oppressor and the oppressed, only antagonism lies ahead. Integration deprives the racial victim of his identity, diluting it as a way of eliminating it. The dialectical stream is often accepted by people who seem in some respects successfully integrated, but it is never a final destination, only a step in the quest for power. The final goal remains complete separation at one end (Nation of Islam) and complete transformation of society at the other (most black radical groups).

This dialectical understanding is engulfing us and has become the mainstream narrative in academia, politics, the media, and even many religious groups. It informs the claims of The New York Times’ 1619 Project. The radical difference between the two streams of thought reflects the ancient tension between the primacy of reason and that of the will. It is the tension between optimism built on the engines of reason and faith, which is aligned with the Western development of the idea of individual freedom, on one hand; and on the other, pessimism and the collectivist pursuit of power, which is aligned with the non-Western understanding of sovereignty and freedom. Ultimately intertwined as they are with such perennial questions, these two streams are also implicated in the great ideological battles of our generation, conflicts between individual freedom as understood in the West and in free market economies, and Marxist-Leninist collectivism and its many manifestations, revisions, and united fronts.

From the beginning of the civil rights movement, these warring camps were in evidence. The collectivist stream eventually captured the high ground with its appeal to the will, to raw emotion, to the most basic instincts of fallen man, and to ideologies that shared the ancient non-Western emphasis on avoiding social death by clinging to the group. Race became the necessary epiphenomenon of class and as such, it was only race that could save us.

Originally published in 1776 Unites

As with pregnancy, so with societies in general. As civilization advances, risk is minimized. Even in the economic sphere, the emergence of insurance and other financial instruments has dissipated risk to a remarkable extent. Widespread wealth insulates individuals from destitution and, through charitable organizations and government institutions, insulates wider communities. In some places, the United States included, these layers of protection are so robust that the prospect of actually dying from starvation or exposure has been virtually eliminated from entire cultures. The fear of death, it would seem, recedes.

As with pregnancy, so with societies in general. As civilization advances, risk is minimized. Even in the economic sphere, the emergence of insurance and other financial instruments has dissipated risk to a remarkable extent. Widespread wealth insulates individuals from destitution and, through charitable organizations and government institutions, insulates wider communities. In some places, the United States included, these layers of protection are so robust that the prospect of actually dying from starvation or exposure has been virtually eliminated from entire cultures. The fear of death, it would seem, recedes. In the contention of CRT, America is an inherently and permanently racist society, whose very foundation is based on racial oppression. Race, not class, gave rise to class stratification and the alienation of “inferior” races. Consequently, America’s political, social, and legal systems are by definition racist and unjust. They are not valid and must be replaced.

In the contention of CRT, America is an inherently and permanently racist society, whose very foundation is based on racial oppression. Race, not class, gave rise to class stratification and the alienation of “inferior” races. Consequently, America’s political, social, and legal systems are by definition racist and unjust. They are not valid and must be replaced. What is true at the personal level is also true at the societal level. Like individuals, cultures need reform. The cycle of corruption and reform is inherent in the human experience. In the history of Western religion, the “Reformation” and the “Counter-Reformation” were watershed events. But even before the dissolution of Catholic Europe, there were the Cluniac reforms, the Hildebrandine reforms, and many others. Contemporary American social and political life is still stamped by reform movements that arose in the late nineteenth century, such as populism and progressivism. The civil rights movement in the postwar era is properly seen as yet another reform movement in American history.

What is true at the personal level is also true at the societal level. Like individuals, cultures need reform. The cycle of corruption and reform is inherent in the human experience. In the history of Western religion, the “Reformation” and the “Counter-Reformation” were watershed events. But even before the dissolution of Catholic Europe, there were the Cluniac reforms, the Hildebrandine reforms, and many others. Contemporary American social and political life is still stamped by reform movements that arose in the late nineteenth century, such as populism and progressivism. The civil rights movement in the postwar era is properly seen as yet another reform movement in American history. This problem has been countered, more or less successfully at various times and places, by the development of alternative schooling options. Religious schools, homeschooling, and charter schools are among the options that have preserved a modicum of freedom within American education. But these and other alternatives have often struggled to find a level playing field, as the legal environment has ranged from favoring public schools (by providing full taxpayer funding) to actively discouraging nonpublic options (by, for example, burdening homeschooling with red tape or strictly limiting charter school numbers).

This problem has been countered, more or less successfully at various times and places, by the development of alternative schooling options. Religious schools, homeschooling, and charter schools are among the options that have preserved a modicum of freedom within American education. But these and other alternatives have often struggled to find a level playing field, as the legal environment has ranged from favoring public schools (by providing full taxpayer funding) to actively discouraging nonpublic options (by, for example, burdening homeschooling with red tape or strictly limiting charter school numbers).

In his

In his  ‘Discovery commences with the awareness of anomaly, i.e., with the recognition that nature has somehow violated the paradigm-induced expectations that govern normal science.’

‘Discovery commences with the awareness of anomaly, i.e., with the recognition that nature has somehow violated the paradigm-induced expectations that govern normal science.’ As recent events demonstrate, the United States is not immune to the plague of violence and civil unrest. But it does have an exemplary record of free elections followed by peaceful transfers of power. The American system—albeit weakened by mistrust, corruption, and disrespect for the rule of law—endures. Even when we aren’t excited about an incoming administration, we can be grateful that the transition does not provoke widespread rioting, a collapse of governmental functions, or civil war. After the election of 1800, a political battle as ugly as any in American history, the victor sought to remind the nation’s citizens of their common aspirations. The words of

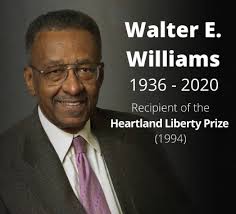

As recent events demonstrate, the United States is not immune to the plague of violence and civil unrest. But it does have an exemplary record of free elections followed by peaceful transfers of power. The American system—albeit weakened by mistrust, corruption, and disrespect for the rule of law—endures. Even when we aren’t excited about an incoming administration, we can be grateful that the transition does not provoke widespread rioting, a collapse of governmental functions, or civil war. After the election of 1800, a political battle as ugly as any in American history, the victor sought to remind the nation’s citizens of their common aspirations. The words of  Especially in his books

Especially in his books